Don't miss the latest stories

Study Uncovers Which Face Coverings Could Be The Least Effective

By Mikelle Leow, 10 Aug 2020

Subscribe to newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Image via Shutterstock

As the scarce N95 masks remain largely reserved for frontline workers, the general public is encouraged to do all it can to help fight COVID-19 infections by using face covers, which can help filter out the novel coronavirus should they be asymptomatic carriers.

However, this advice—no matter how many times it is drilled into people’s heads—doesn’t answer some questions, like which face covers aren’t so effective. So when a professor at the Duke University’s School of Medicine partnered with a local group to purchase masks in bulk to distribute to the community, researchers in his team decided to find out once and for all which types they should not invest in.

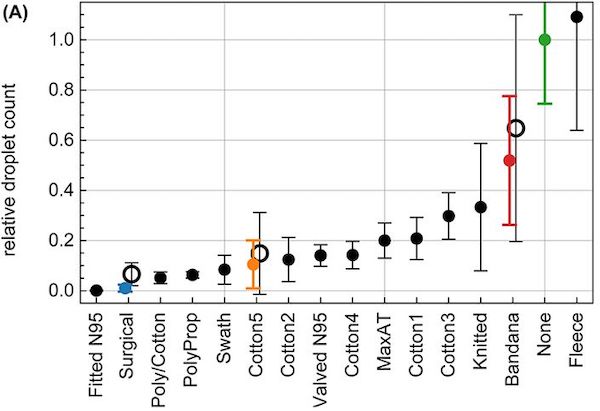

The team performed a simple test involving 14 common types of masks, as well as a laser beam, black box, and cellphone to observe the diffusion of respiratory droplets during speech.

“The laser beam is expanded vertically to form a thin sheet of light, which we shine through slits on the left and right of the box,” Martin Fischer, one of the researchers, described to CNN. The team would then have a speaker talk into a hole at the front of the black box, and the cellphone’s camera would capture how much light from the laser beam is passed around the box through respiratory droplets.

Participants were asked to speak without a mask at first, and then repeat the experiment with the protective garment. Each face mask went through 10 rounds of testing.

Finally, a computer algorithm would count the droplets in the footage.

To their surprise, the researchers discovered that there’s little point in wearing certain types of masks.

In their findings published in Science Advances last Friday, the team noted that the most effective covering of the 14 was, predictably, the N95 mask. This was followed by three-layer surgical masks and cotton variants, the sort people craft at home.

Alas, the least effective option turned out to be neck fleeces, or gaiter masks. The team even found that more respiratory droplets were transmitted with fleece garments on, as opposed to when no mask was worn at all, since its material tends to break down larger droplets into smaller—and therefore, more transportable—ones.

From their observations, they have also advised against using folded bandanas and knitted covers.

Image via Emma Fischer, Duke University (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Image via Emma Fischer, Duke University (CC BY-NC 4.0)

[via CNN, images via Emma Fischer, Duke University (CC BY-NC 4.0)]

Receive interesting stories like this one in your inbox

Also check out these recent news