‘Copyright Trolls’: The Unseen Tactics Lurking In The Backdrops Of Online Photos

By Mikelle Leow, 02 Nov 2022

Photo 113032861 © Jakub Jirsak | Dreamstime.com

The picture is shadowy for online imagery as far as copyright issues are concerned. It’s not uncommon to come across incidents of people who have been caught in legal trouble for misusing someone else’s work, whether intentionally or not. The underbelly of it all, though, is far more bizarre and unknown.

Even downloading a Creative Commons image could land someone in trouble. Heck, the White House’s former photographer himself was accused of breaching the copyright of his own photo this year (read on for more details).

Creators who rely on certain image-crawling services could be getting less than they should be receiving in damages—and even lose favor with the public, considering the hard-handed tactics employed by their solicitors.

DesignTAXI was roped into this complex web upon receiving a warning from a so-called “copyright troll.” The dispute was eventually tossed because it was proven that we were, in fact, permitted to use the photo in question. The experience was frustrating, nonetheless.

Once we were incepted into this world, the vortex just kept expanding.

In a time of recovery, we hope to deliver clarity to those who need answers in the messy areas of copyright. Since it’s impossible to squeeze everything into one article, we’ve published a three-part investigation, each piece considering the best interests and concerns of photographers and everyday users.

If you know anyone who is affected, pass it on. This article is also free for anyone to republish (note: stock images ought to be separately licensed)—with attribution and link to this page—so that the broader community can learn from these experiences.

Introducing the “copyright trolls”

It’s ever inspiring to watch how the creative world evolves each day—and among these heartfelt moments are when Good Samaritans make their work available for the public to use for free. However, there are a few bad actors in the community who, although claim to also be giving away their images, aren’t doing it for goodwill.

They go down the route of planting their photos into free-use image banks, in hopes to exploit loopholes in outdated CC licenses (anything before CC 4.0—more on that later). They engage image-crawling software—which scour the web for usage of the photos, and often work with law firms to take action on so-called violators.

Then, they wait to see who bites, and strike unsuspecting individuals en masse in one fell swoop.

This is a strategy commonly employed by a class of pros known as “copyright trolls.” They knowingly seed attractive content into places that the public can easily get to, leading people to reuse and share it so that they can catch them for violating copyrights. Victims are coerced into paying fees, or they’ll purportedly risk forking out more when the matter is taken to court.

The US District Court describes a “copyright troll” as someone who “plays a numbers game in which it targets hundreds or thousands of defendants seeking quick settlements priced just low enough that it is less expensive for the defendant to pay the troll rather than defend the claim.” These parties appear to be more interested in “the business of litigation,” as opposed to the best interests of creators.

Sue-pendous

The dedication of these entities is eye-opening. As of 2019, one lawyer named Richard Liebowitz filed 1,210 copyright complaints on behalf of photographers and other copyright holders in New York’s federal trial courts, seeking up to a purported US$4.5 million from US individuals and companies. Of 700 cases filed in Manhattan federal court, 500 of them were “resolved without any substantive litigation,” Reuters reported then.

One of his clients, a Germany-based photographer, invented his own software to track down alleged violators who had made errors in their attribution. Most of the photographer’s images were, interestingly, licensed under the outdated CC-BY 2.0 license, which is far less forgiving and doesn’t give users a chance to fix any mistakes to their captions, even if they are apologetic and want to make the edits.

Liebowitz is now suspended for exhibiting a pattern of “failing to comply with court orders and making false statements to the court,” as per the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. His aforementioned client has since been restricted from sharing images on Wikimedia Commons, which warns that subsequent upload attempts by this photographer will be “speedily deleted.”

Even former White House photographer Pete Souza wasn’t spared from such antics. In August, he revealed that he’d been threatened with legal action for infringing the copyright of his own photo of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, which was posted on his website. Luckily, the image crawler withdrew the dispute when he pointed out that official White House photos do not hold any copyright.

“You can’t make this s**t up,” Souza lamented in an Instagram post. He suspects his photo was included in the company’s archives without his knowledge—since public domain images aren’t protected—in hopes it would be used by many.

Higbee & Associates, which oversees alleged copyright infringements for photos owned by Agence France-Presse, told Fast Company that about “75% to 80%” of its cases are resolved outside of court.

Image tracker CopyTrack purports to have scanned 65 million pictures, made US$63 million worth of “stolen image claims,” and won cases in 115 countries.

On its website, Polish service PhotoClaim asserts it has won court cases in 18 countries—enforcing mostly German law on alleged infringers. One of its lawyers has gained so much notoriety that there is a dedicated website cautioning others about his letters.

Some other players of this game—creatives themselves—have boasted about such practices being their “main revenue.”

Often using heavy-worded and complex legalese in their letters, “copyright troll” lawyers frighten users into settling quickly.

Solicitors are alerted of possible violations via reverse image search bots they work with, like PicRights, ImageRights, PhotoClaim, Pixsy, and Copytrack, then issue takedown notices to so-called offenders in large volumes.

Delivery Status Notification (Failure)

Interestingly, the initial cease-and-desist document doesn’t always get properly delivered. It could be that there’s a typo in the recipient’s email address (discovered later when subsequent letters come in), or the letter goes straight into their junk folder.

Crucially, the contents of these emails are extremely time-sensitive because there are penalties for late responses. The screenshot above shows an initial warning sent to DesignTAXI that ended up in our spam folder (the allegations were deemed invalid, and eventually dropped as usage rights were ultimately proven). Note that Gmail, the most-used email client in the world, flagged this up as junk.

Here’s the kicker: Subsequent letters DO turn up in recipients’ inboxes, and they’re perhaps the first instance where people are made aware of an impending dispute.

Since the alleged infringer didn’t remove the offending photo nor acknowledge the first email in time, they now not only have to reimburse the lawyer and their client with increased fees, but their non-reply will also be assumed as a “non-obligation.”

It turns out it’s not us, it’s him.

Berlin lawyer Tim Hoesmann of Kanzlei Hoesmann, who has dealt with numerous letters by the same attorney and his associate, tells us that it’s standard practice for lawyers to send physical copies of letters, on top of emails, to their recipients.

However, “[these] letters are often only sent by email,” Hoesmann notes. This makes it “often impossible for the sender to determine whether the letter has been received at all.”

“As the sender, however, you have to prove that the letter has been received. Reputable lawyers regularly send their letters by normal letter.”

Photo 117231082 © Prostockstudio | Dreamstime.com

A win-lose-lose?

The “offender” is advised to comply with the demands as costs will only climb if the situation is eventually handed to the court. “Image recovery” service PhotoClaim echoes this on its site, writing: “We prefer to resolve each case as soon as possible with lower costs to cover for you. The best is to get in touch and follow lawyer advice.”

Lawyers and photo-tracking systems ask “infringers” to refrain from contacting the clients themselves as it could cause the photographers’ “creativity” to suffer. “That’s why they chose us to take care of their rights and keep their minds free,” the company elaborates on its FAQ page.

What’s strange is that some people on the receiving end of these letters have pointed out that they had properly licensed the “offending” photos, which suggests not everyone who is targeted has violated a copyright. When the accused dig out their records and present proof, the lawyers sometimes go away.

“We responded with proof that the photographer himself had sent us the image in question,” writes one person. “We have now invoiced the company for our time wasted on their refuted claim.”

Some photographers agree that there are instances where the use of an image by someone else may be wrongfully flagged up as infringement. “My heartfelt apologies for my mistake [if that happens],” wrote one photographer in a PetaPixel op-ed. “If you forward the license agreement or receipt to my lawyers, we will drop the case and I will fully refund your original license payment… I have made an erroneous accusation before, and I felt terrible about it.”

Italian journalist Giovanni Franchini, who has been fervently investigating these matters, tells us that what bothers him the most is how “copyright rules are created to protect the authors of intellectual works from the abusive exploitation of others,” and yet some image crawlers have made it their mission to monetize the law.

“With software, I [in the mind of a copyright troll] can find any image, whether of a petrol station, or a sign… or a provincial road. These are generic photos. But I write to whoever has published them and I say that he has violated the copyright and now he owes me $300, $600, $1,000 dollars! I decide the violation, and I set the price.”

Franchini brings up the rationale behind mass emailing systems deployed by these platforms. “Working online, I know how it works. If you send 10 emails and one [person] accepts your proposal (in this case they agree to pay you), you know that if you want to be paid by 100 people, you have to send 1,000 emails. And that’s what these companies do. They are [focused on] business; the protection of photographers has nothing to do with it.”

When he interviewed one of PhotoClaim’s co-founders and challenged the platform’s business ethics back in 2020, she justified that “few people… understand how much it costs to create a high-quality photo… Therefore, there are few people who would answer politely to a simple letter asking to pay the license fee.”

“As long as this is the reality, we work with lawyers and leave the courts to decide on justice,” she continued.

Money talks

There are grounds for the niggling suspicion that “plagiarism trackers” aren’t putting their own interests first over their clients’.

Image detection platforms pocket a large slice of net recovery fees, claiming 45–55% of compensation for successful settlements.

These are just the numbers declared on their websites. Photographers may not get the full picture because only the lawyer and the party who received the warning will be privy to the actual fees.

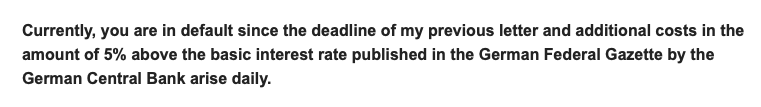

A new breakthrough in Italy sheds more light on the pricing strategies of PhotoClaim. On October 3, 2022, the Italian Competition & Market Authority published a bulletin noting that it has formally prohibited the service and its German lawyer—the same one who sent us the warning—from issuing “misleading” letters in the country. In its notification, it disclosed the company’s official payment model, writing:

“PhotoClaim and the lawyer… demand payment of a fee for their services only if the legal action is successful. In particular, PhotoClaim receives from the photographer a percentage between 35% and 45% of the sum paid as compensation for damages, as well as 50% of the sum paid as legal fees. The lawyer [name redacted] receives the remaining 50% of the legal fees.”

In our case, at least, the legal fees curiously exceeded the damages owed to the creator, the originator of the work.

Based on the above example, resolution may have been speedier for the creator had they personally contacted the defendant for compensation. The amount in question, bumped up from hundreds to thousands by the legal fees, will inevitably complicate and stall the process of settlement.

Click to view enlarged version

Screenshot of bulletin by the Italian Competition & Market Authority dated October 3, 2022, with English translation on the right. Click to view enlarged version

It’s now apparent that the platform collects 50% of the legal fees, while the lawyer receives the other half.

The lawyer also asks that all funds be directly remitted to his bank account. Meanwhile, his client will only receive their settlement on the 30th of the month.

Imagine cutting out the middleman and claiming the full amount in damages. The process would go by more amicably and swiftly, as opposed to having to demand hefty add-on fees from the defendant that they might not be able to afford.

Not forgetting, after a bitter and drawn-out exchange between the lawyers and alleged violators, it won’t reflect nicely on the photographers, too, since they—not the lawyers—are the plaintiffs named on legal records.

Spelling trouble: Watch out for typos, and read the fine print

Photo 4038549 © Prochasson Frederic | Dreamstime.com

The slightest oversights, things as innocuous as a typo in the line of attribution or the wrong linkage, could nudge users into the line of sight of nitpicky lawyers assigned to take action on them by reverse image search tools.

Some of the most public cases are those involving concert photographer Larry Philpot, who since 2014 had filed over 150 complaints in federal courts against users who either left out attribution, or did remember to give credit—though not exactly in the way that was asked by the photographer.

In one instance, the defendant had featured Philpot’s photo of Willie Nelson with the caption, “Flickr/BehindTheMusic.” That wasn’t sufficient for the photographer, who had deemed the proper (and only) way to spell it to be: “Willie Nelson getting ready to perform. Farm Aid 2009. Photo by Larry Philpot, [www.soundstagephotography.com].”

A separate case from this year saw a student website being targeted for using a photo of a generic medical syringe that the group had obtained from a popular CC website. The team did ensure to accredit the photographer, but missed out on the terms to link up a specific page in the owner’s website as well as indicate the image’s licensing terms, as specified by the photographer in the fine print. For that, it was asked to pay over US$5,000, according to the Student Press Law Center, which shared the scoop.

The “safest” Creative Commons licenses: CC BY 4.0 and CC0

Photo 214580199 © Vadim Rodin | Dreamstime.com

The prevalent Creative Commons 2.0 license—which generally allows the copying and remixing of content—was introduced in 2004. Its followup, 3.0, was established in 2007. Still, these licenses remain HEAVILY in use while their successor, the 4.0 Creative Commons license, has been available for nearly a decade.

Flickr, where many photographers share their images, currently only supports 2.0 licenses. It remains uncertain when adoption for the newer versions will take place.

“The change from Creative Commons 2.0 to Creative Commons 4.0 is something that we are currently looking into implementing and we are actively meeting with Creative Commons to discuss a strategy for moving to 4.0 licenses,” a spokesperson for Flickr tells DesignTAXI.

“Although we do not have a current timeline, we’re hopeful this is something we can implement in the near future. When this happens, we’ll be sure to update our community of any changes,” the photo-sharing service adds.

The thing with older versions like the 2.0 and 3.0 licenses is that if you don’t fully follow the usage terms stipulated by the copyright holder—such as citing a specific URL—your license could be terminated immediately. That means you will have lost the right to publish the material, and any desire to remediate things won’t matter. It also gives “copyright trolls” an in to catch more prey.

4.0 is much more forgiving. It allows the “infringer” a 30-day window to fix a violation. Following that, their license will automatically be reinstated.

Further protecting the user, CC licenses beginning from 4.0 are universal and share the same usage terms worldwide. Before, there were “ported” types that limited usage to regions.

To be clear, the 2.0 and 3.0 licenses still work. The Creative Commons Organization, however, emphasizes that the latest version is recommended “in all cases… as it reflects the latest thinking of Creative Commons and its global network of legal experts.”

With CC0–AKA public-domain imagery—some precaution is still necessary. There’s the risk that the material has been labeled to be under the “public domain” by a third party who doesn’t know much about copyright law. It’s also a good time now to stress that putting an image out on the internet, be it through social media or a blog, doesn’t make it “public domain.”

In 2019, one photographer was ensnared in a legal battle for reusing a photo he had found on Unsplash. As you may know, the site promises to grant users an “irrevocable, nonexclusive, worldwide copyright license to download, copy, modify, distribute, perform, and use photos” across its repository. However, it was later discovered that the image was put there by a third party who wasn’t the copyright holder.

Pseudo-penpals: You can be sued from other corners of the world

Photo 91347809 © Dezzor | Dreamstime.com

Now we’re entering tricky territory. The concept of cross-border litigation is a huge part of the confusion surrounding internet copyright law. And, yes, it’s more than possible to face legal repercussions with someone who lives in another country or continent.

Two words: Berne Convention.

Copyright lawyers apply the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works treaty to assess the usage of protected works abroad. Adopted in 1886 and overseen by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the Berne Convention is the closest semblance of international governing copyright standards yet. It’s signed by 181 states worldwide, ensuring a more harmonized copyright law and giving contracting parties equal treatment in other member states.

The only countries or regions that aren’t subscribed to the Berne Convention are Angola, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Kosovo, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Myanmar, Palau, Palestine, Papua New Guinea, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Taiwan, and Timor-Leste. For these areas, only their specific territorial copyright laws apply.

One of the most significant traits of the Berne Convention is that copyright is automatic for parties of the treaty. There’s no requirement for citizens of participating countries to file formal registrations in other member states—protection exists the moment the work is created. There are a few exceptions, however. The US, for instance, is a Berne Convention member country and recognizes its near-worldwide enforcement, but the nation continues to double down on the registration of copyrights for them to hold weight in court and grant statutory damages and attorney’s fees.

The Berne Convention is also based on the notion of “country of origin,” meaning the country the work was first published in. And with the digital world being practically borderless, here’s where there’s a gray area. The internet age means content can be published in multiple regions at once. Courts have thus struggled to define a determining country of origin because anywhere and everywhere can be the country of origin if the material is popping up simultaneously around the world.

Copyright law is territorial by nature, so this adds to the confusion. The Berne Convention promises cross-country benefits, in that basic rights are applied to foreign member states (“minimum standards”) and non-domestic creators receive the same protection as locals for their work (“national treatment”). However, infringements that take place in another jurisdiction will be judged according to the terms of the foreign country.

While this set of rules strives for equal copyright protection of creators everywhere, the act is also heavily enforced by the so-called “copyright trolls” who apply their own countries’ laws on “offenders.”

Photo 11633873 © Joachim Wendler | Dreamstime.com

“I can’t understand why an American who took a photo in Italy is using a German firm to pursue a British website.”

Such are the disgruntled words of one person on the PistonHeads.com forum. It just looks to be a geography joke that many consumers cannot get.

Depending on which judge oversees the case that day, though, they may agree that being able to access the infringing source on the internet in another country counts as a violation there too.

Tim Hoesmann of Kanzlei Hoesmann recounted a case where his client, an American business, was accused by a German legal firm of violating the copyright of a Dutch photographer, and it was enforcing German law on his client. Hoesmann said the picture in question could be licensed from official channels for €29 (US$28.50).

Hoesmann looked up the Dutch photographer’s website and learned that his work’s terms and conditions are based on the regulations of Dutch copyright law.

The plaintiff’s lawyer, however, used a German calculation table called the Mittelstandsgemeinschaft Foto-Marketing (MFM) list and charged the American business for the photo’s online use, worldwide application, lack of accreditation, and its usage over 10 months, ringing the number up to €3,041.50 for the €29 photo.

“He always refers to German law,” Hoesmann tells us. “A reference to Germany is regularly given if one of the parties is based in Germany or if the site has a thematic reference to Germany.”

Hoesmann explains that some courts may actually side with the argument that publishing unauthorized material on a website accessible in Germany makes it offensible in Germany.

“For some courts, it is in fact sufficient that the web pages can be accessed in Germany,” he tells us. “This is the case for every page worldwide.”

In January 2020, journalist Giovanni Franchini woke up to a copyright letter from a German law firm that had run a search on PhotoClaim and flagged up a photo he’d obtained from a press kit.

Over 200 comments have flooded his blog post, many of which come from people who have received notices like his. It’s obvious that many aren’t getting the answers they need. Since then, Franchini has published seven more articles on copyright law, as well as assumed a role of helping others in a similar plight seek legal counsel.

It was the first time in the reporter’s career of 35 years that he had encountered such hostile language in a takedown request. Perhaps more than anything, Franchini was struck by how the attorney was threatening him with German law. The photographer whose copyright he’d apparently infringed was Italian and based in Italy, and with Franchini himself being Italian and residing in Italy, shouldn’t he have been dealt with by Italian law?

“Even if there is a reference to Germany, you have good chances of defense,” Hoesmann reassures us. “The background to this is that it is often a matter of mass warnings and these are viewed strictly by the courts.”

Why Germany?

Time and time again, Germany chronically turns up as the unofficial headquarters for copyright trolls. Filing cease-and-desist letters is the “national pastime” of Germans, one blog claims. Just what is it about this jurisdiction that makes it so attractive?

When a claim is filed in German civil court, it’s a quick and fairly affordable process—there’s no need for a jury, pre-trial discovery, or pre-trial witness statements.

Christian Montana, an Italian lawyer who specializes in international law at his practice Gardenal Camatel Montana, conjectures that a standardized fee table for photographers in Germany (called the MFM table) may also help, as the objectivity can speed up the process for calculating damages.

“This makes it easier for trolls to obtain court orders quickly… without having to provide evidence on the damages actually suffered,” Montana tells us in an interview. “It is then up to the defendant to bring an opposition in court, which they often choose not to do as it would be too costly, so trolls have had a lot of winning orders, in fact.”

According to Thomson Reuters Practical Law, the nation tightened its measures to quell the pattern of “alleged rights holders” firing high volumes of cease-and-desist orders across the internet for monetary reasons. These safeguards, introduced in 2013, weren’t so effective, reported eBay, which had still encountered multiple “frivolous, harmful” affronts on its online merchants.

“In Germany, a company can send a competitor a cease-and-desist letter if they feel the competitor is not complying with German laws. Unfortunately, this rule is sometimes abused and smaller enterprises pay the price,” eBay’s Main Street advocacy group wrote. “Cease and desist letters are sometimes sent out by parties who have no actual interest in competitive activities, but are instead attempting only to collect a fee.”

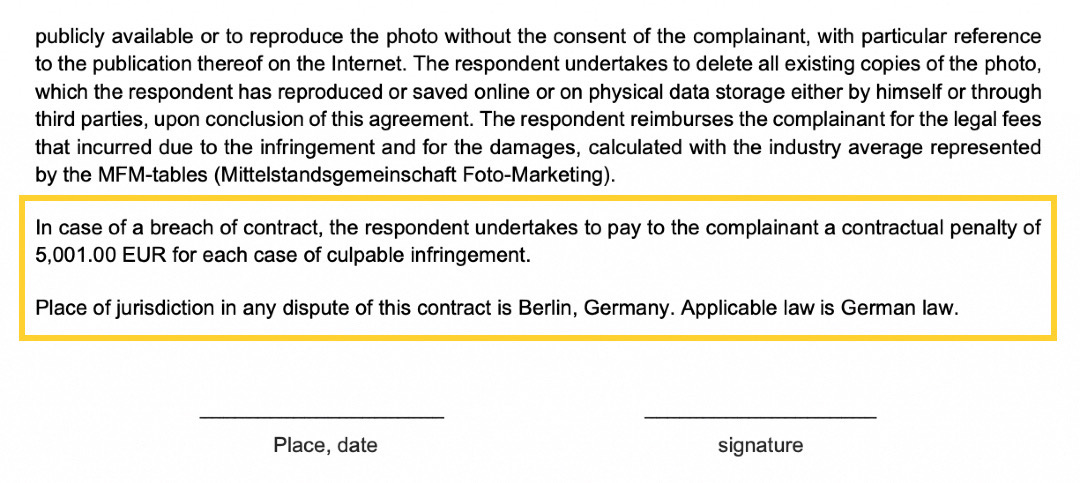

As indicated in the cease-and-desist example above, signing it subjects the defendant to German jurisdiction, wherever they may be.

DesignTAXI reached out to the German Federal Ministry of Justice for comment.

Wait. Is all this legal?

If you’re on the receiving end of these letters, unfortunately, they’re valid. It’s true that using an image without authorization, even if by accident, or not properly adhering to the terms counts as infringement. Some people continue to set up “traps” because these tendencies keep happening, and others continually fall into them.

Copyright trolls are “totally legal,” Chip Stewart, a professor at Texas Christian University and a lawyer who studies these strategies, told Bloomberg. “It’s just evil.”

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), the US law that watches over copyright issues on the internet, does protect exploited individuals from “trolls” to some degree. It notes: “Any person who knowingly materially misrepresents… that material or activity is infringing… shall be liable for any damages, including costs and attorneys’ fees, incurred by the alleged infringer… as the result of the service provider relying upon such misrepresentation.”

On top of this, PhotoClaim and its lawyer were restricted from issuing “misleading” copyright takedown notices in Italy, a move Franchini calls unprecedented for the sphere of copyright trolling.

The photo-crawling platform was fined €35,000 (US$34,000) and convicted for failing to manage the professional conduct of the German lawyer, who was also fined €10,000 (US$9,700) for not upholding the “high degree of diligence required by professionals in the legal protection of online copyright.” The amounts were determined in proportion to how much the two parties had declared to be earning in Italy in 2021.

Italian authorities began investigating the offenders after a small business they had gone after had agreed to pay up €2,000—after negotiating the fees down from €3,000—and received a second letter asking for €6,000 for breaching their cease-and-desist order. The complainant filed a report to the Italian Competition Authority.

“We will never again see letters from [the lawyer and firm] touring Italy,” Franchini triumphs.

Photo 20449451 © Haywiremedia | Dreamstime.com

There’s more than meets the eye…

If the horizon already looks too cloudy so far, deep in the underbelly of the industry lies a core we hadn’t yet shed light on: the very crawlers that spider the vast webs of images.

Are tracking and monitoring performed on-demand or ceaselessly 24/7 around the clock? Are entire websites being duplicated in the process? Are copyright, privacy and data protection ethics being contradicted?

As we step further into the abyss, more mysteries unfold.

This story is part of a series investigating the impact of copyright trolls on the industry. See our other features:

- For Image Users: Got A Copyright Infringement Notices? Here’s What You Have To Do

- For Photographers & Creators: Was Your Photo Stolen? Regain Control Without Hurting Your Online Reputation